**CLICK ON PICTURES TO ENLARGE**

Morocco - the Star of

the Sahara, the Gateway to Africa - is a nation with a long and rich history of

cultures coming together. With its blend

of indigenous Berber traditions, Arab influences, and European arrivals, Morocco

is both sophisticated and exotic – a feast for the senses, with a rhythm all

its own.

Morocco - the Star of

the Sahara, the Gateway to Africa - is a nation with a long and rich history of

cultures coming together. With its blend

of indigenous Berber traditions, Arab influences, and European arrivals, Morocco

is both sophisticated and exotic – a feast for the senses, with a rhythm all

its own.

Morocco is located in northwest Africa and many people think it’s just another third-world country. That would be a bad assumption. It is true that Morocco is a land of timeless traditions, but in many respects it is a very progressive country. King Mohammed VI has led efforts to make changes in women’s rights and in Morocco’s infrastructure. For example, women are encouraged to get an education and a paying job outside the home and they now have the right to initiate divorce proceedings – big changes from longstanding Muslim tradition of male dominance in all things.

Infrastructure

improvements are seen everywhere. Every

city, town and most villages have ongoing rebuilding, restoration and

renovation projects, as well as new roads and bridges – all with beautiful

streetlights. The railway system is

being improved, including new high-speed train services. Tangier’s harbor has been updated and greatly

expanded, making it the largest port in all Africa. The King set a goal of having the country free

from use of fossil fuels, and Morocco is well on its way to 100% solar

power. Last – and most noticeable –

Morocco has banned the use of plastic shopping bags; result – almost no litter!

Morocco is full of surprises:

Morocco is full of surprises:

- Before the rifts that split the continents in the late Triassic age, New Jersey shared a land border with Morocco. Their coastlines now face each other across 3,700 miles of Atlantic Ocean.

- The national costume, the djellaba, is unisex, a pull-over worn by men and women alike, which distinguishes not gender but marital status by its color and decoration.

- In 1786, Morocco became the very first country on earth to sign a treaty with the United States, recognizing it as a sovereign nation.

- Despite being associated with desert imagery, the Atlantic Ocean serves as Morocco’s entire western border, and the Mediterranean Sea outlines its northeast, which explains how Morocco became the world’s biggest exporter of sardines.

- Escargot is not a delicacy for the rich or reserved for fine dining; prepared snails are a popular finger food easily found in souks and humble cafes.

- The highest ski resort in Africa is in Morocco’s High Atlas Mountains, even though the average annual snowfall never exceeds eight inches.

- There is a dentist for every 800,000 residents in Morocco, where tooth extraction is so common, you will see open-air dentists in souks literally plying their trade with pliers.

- The glossy burled thuya wood used for the dashboards and interiors of luxury cars by Mercedes, BMW, and Rolls Royce—including the famed Silver Ghost—comes from only one place on Earth: the Atlas Mountains of Morocco.

- During the Iraq war in 2003, Morocco offered to send 2,000 monkeys to help US allies by detonating landmines; the offer was not accepted.

- In heavily Muslim Morocco, it is legal to own a Christian Bible, but not if it’s written in Arabic.

- With its desert often compared to Mars, it is fitting

that when a 700,000-year-old meteorite from the red planet crashed to

earth in 2012, it fell in Morocco.

And off we go on an adventure to another world! With good friends Jo Wilson, Carol Bennett,

and Dennis and Vicky Shepard, we traveled with Overseas

Adventure Travel. Not sure what to expect - perhaps we will ride a

camel, camp in the Sahara, explore ancient towns, and drink tea with Berbers. Our trip started with a very long plane

trip: Columbia to Atlanta to Paris to Casablanca, with long layovers, long

lines, and lots of traffic. After 20+ hours of travel time, we arrived

exhausted about 8PM local time.

After night’s rest in

Casablanca, we headed for the Rif, the region bordering the Mediterranean Sea

and known for its atmospheric and beautiful old towns. The

drive was relaxing, with lots to see: mountains,

coastline, rocks, gorges, small farms, olive groves, and oak forests.

And storks. The white stork is a huge bird that builds

huge nests in very high places. It is

known as a long-distance migrant, wintering in Africa and nesting in Europe. It appears that many of these birds have

chosen permanent residence here.

We stopped for lunch, at a very local, very authentic, roadside diner. At first glance, it seemed to be a meat market, but what a treat it turned out to be.

The family had been busy cooking for us – the tradition Moroccan chicken tagine with vegetables, and a side of beef kabobs. Tagine is a slow-cooked savory stew, named after the earthenware pot in which it is cooked. Today it was a rich mix of meat and vegetables, but other versions include beef, lamb or fish, sometimes with fruit.

Desert was a just-picked local orange – without a doubt, the best we’ve ever tasted. Happily, oranges were in season and we frequently were served sliced oranges sprinkled with cinnamon - yummy.

A bit further down the road we stopped for a look at a cork oak forest. Cork is harvested from these trees by careful removal of the cork cambium once every 8-10 years.

CHEFCHAOUEN is the Jewel of the Rif Mountains, also known as the Blue City. It is a delightful town nestled in the hollow at the foot of the Rif Mountains. It features blue and white-washed buildings, small squares, ornate fountains and houses with elaborately decorated doorways and red tile roofs. It was founded in 1471 by descendants of the Prophet Mohammed as a stronghold against the Portuguese. Chefchaouen is esteemed as a holy town, with eight mosques and several monasteries.

Our lodging here was Riad Darechchaouen, a family home that

has been remodeled and enlarged to become a guesthouse. We were welcomed by the owner-manager, who

entertained us with our first taste of Moroccan mint tea. This was a most pleasant spot – views of the

nearby mountains, nice gardens, interesting décor, and rooms in traditional

Moroccan style.

It was just a short walk to Chefchaouen’s medina - the old town or core of the city, where the first settlement got started. It is mostly walled-in, a maze-like complex of small streets running through the oldest part of town. Lots of blue color! Blue painting started here about 100 years ago, to help guard against deterioration of the stucco walls. The blue color represents heaven, but it can only go as high as the ladders will allow.

It was just a short walk to Chefchaouen’s medina - the old town or core of the city, where the first settlement got started. It is mostly walled-in, a maze-like complex of small streets running through the oldest part of town. Lots of blue color! Blue painting started here about 100 years ago, to help guard against deterioration of the stucco walls. The blue color represents heaven, but it can only go as high as the ladders will allow.

All over town, there are many fine houses with carved and decorated doors and all sorts of interesting people walking everywhere.

Small shops abound along the narrow streets. There are more than 100 weavers’ workshops, famous for the woolen jellabas (traditional hooded cloaks) that are woven here, as well as for the red and white striped fabrics worn by the women of the Jeballa tribe in the mountains to the west. (See photo above - woman with striped shawl and straw hat.)

Fountains are common, dating back to a time when they provided all water to residents of the town. One of the most distinctive fountains is Ain Souika, set in a recess in the district’s main street; it has a semicircular basin and interlaced lobed arches.

Last, but

not least, Chefchaouen has a most interesting laundromat – a shelter covers a trough diverted from the river,

providing a steady stream of icy cold water.

Local women come here to wash clothes (and entertain tourists).

HOUMAR is a small Berber mountain village of about 350 inhabitants. Here we were welcomed into the home of Mohammed and Ihsaan and their two-year old daughter Zenab. They showed us around their home and told us a little about their lives; life here is simple, but hard. While we visited, our #1 guide (Nourredine or Nory) demonstrated his fancy technique for pouring mint tea – known locally as Berber whiskey. Notice that everyone is wearing coats indoors - many homes are not heated!

Ihsaan put us to work helping prepare lunch. It was quite a feast – fava bean soup, vegetable tagine (veggies from their garden), Moroccan chicken with figs, cauliflower and cabbage, homemade bread, and flan for dessert (milk from the father’s cow).

Two-thirds of

Moroccans are, in cultural and linguistic terms, Berbers. Thought to be descendants of people of mixed

origins – including Oriental, Saharan and European – the Berbers do not make up

a homogeneous race. Berbers have been

around for at least 4000 years, with various groups settling in Morocco at

different times. By finding refuge in

mountainous regions, they survived several successive invasions – of

Mediterranean countries, the Arabs, and later, the French and Spaniards. They still speak several dialects and

maintain distinct cultural traditions. Many

Berbers were traders in the earlier times, but today most are farmers,

including this village of Berbers who have settled in the Rif Mountains of

Northern Morocco.

Two-thirds of

Moroccans are, in cultural and linguistic terms, Berbers. Thought to be descendants of people of mixed

origins – including Oriental, Saharan and European – the Berbers do not make up

a homogeneous race. Berbers have been

around for at least 4000 years, with various groups settling in Morocco at

different times. By finding refuge in

mountainous regions, they survived several successive invasions – of

Mediterranean countries, the Arabs, and later, the French and Spaniards. They still speak several dialects and

maintain distinct cultural traditions. Many

Berbers were traders in the earlier times, but today most are farmers,

including this village of Berbers who have settled in the Rif Mountains of

Northern Morocco. Farming here is hard

work; crops are grown on the steep slopes by building small

terraced fields along the mountainsides.

Rock walls retain the soil, which is carefully fertilized each year with

manure and composted plant material.

These soils are rich enough in some areas to allow two grain groups to

be grown each year: barley, then

wheat. Broad beans, peas, chickpeas and

lentils are also important.

Farming here is hard

work; crops are grown on the steep slopes by building small

terraced fields along the mountainsides.

Rock walls retain the soil, which is carefully fertilized each year with

manure and composted plant material.

These soils are rich enough in some areas to allow two grain groups to

be grown each year: barley, then

wheat. Broad beans, peas, chickpeas and

lentils are also important.

Much of the farming

is still done by manual labor. Fields are cultivated using wooden or

iron-tipped plows pulled by a team of horses or a mix of horses, mules or donkeys.

Crops are harvested by hand and once dry, are threshed by treading with teams

of donkeys or mules. Field size is generally quite small and the majority of

farmers farm no more than 5 acres. The

farms must have access to irrigation water, usually from a nearby mountain

stream.

Fruit crops

include: walnuts, citrus, grapes,

olives and dates. Vegetables include

tomatoes, green peppers, water melons, cucumbers, eggplant and root vegetables

such as sweet potatoes and turnips. Olives are especially popular - we were served olives all all three meals each day.

Morocco is the leading producer of hashish (cannabis), in spite of government efforts to limit its cultivation. They’ve not had much luck, as the prosperity of the cannabis farmers contrasts starkly with small-scale farmers elsewhere in the country, who have suffered from several years of drought.

Morocco is the leading producer of hashish (cannabis), in spite of government efforts to limit its cultivation. They’ve not had much luck, as the prosperity of the cannabis farmers contrasts starkly with small-scale farmers elsewhere in the country, who have suffered from several years of drought.

Agriculture is still

the number one source of income for the Moroccan economy, followed by mining of

phosphate minerals and tourism. Sales of fish and seafoods are important as well. Mining and other industry contribute about

one-third of the country’s annual gross domestic product.

TETOUAN, sometimes called the ‘daughter of Granada’ or ‘little

Jerusalem,’ is a seaside town that was inhabited by Jewish refugees from

Granada and Moors from Andalusia. The

city has a rich mix of cultures and traditions – Roman, Andalusian, and

European. Founded by Andalusian refugees

in the 15th century, the city’s labyrinth of squares, markets, and

beaches still maintains its old-world charm.

Tetouan is located at the mouth of a river and surrounded by orchards of

almond, pomegranate and cypress trees.

Tetouan became the

capital of the Spanish protectorate of Morocco from 1912 to 1956. The city managed to develop a harmonious

relationship among the Muslims, Jews and Christians who live here. Muslims are the majority today; the Iglesia de Bacturia is the sole

surviving Catholic church (built in 1926).

It may be the only place in Morocco where church bells chime every hour;

services are still held in Spanish.

Tetouan’s medina (old town) is surrounded on three sides by walls; it contains 36 mosques and sanctuaries,

seven gates and untold numbers of alleys and arches. This medina

might be one of the smallest in Morocco; it is also one of the best

preserved. Largely untouched since the

17th century, this Spanish-influenced medina has been named a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Walking through its various ethnic quarters – Andalusian, Berber and

Jewish – is to experience Morocco’s multicultural history firsthand.

The medina is, above all, a marketplace, and just about everything is for sale here, much of it still made by hand. In spite of the rainy day, its narrow streets and tiny storefronts explode with color. Vendors offer carpets, jewelry, and leather, as well as local dishes for sale from food carts.

The medina is, above all, a marketplace, and just about everything is for sale here, much of it still made by hand. In spite of the rainy day, its narrow streets and tiny storefronts explode with color. Vendors offer carpets, jewelry, and leather, as well as local dishes for sale from food carts.

We stepped inside the

communal bakery, a common feature of every Moroccan neighborhood. There are big wood-burning ovens where bread

is baked all day long, but local women also bring their bread to be baked –

much easier than having a hot oven in their homes.

We also enjoyed

watching a man spin thread from the fibers of the yucca plant. He had long strings hanging all along the

walls; he reeled them in to make all sorts of items from ‘Moroccan silk’ –

ropes, belts, you name it!

Just outside the

medina, the Royal Palace is a 17th century building that is a reflection of Hispano-Moorish architecture. The ornate main gates give some idea of the

grandeur within, but the palace is not open to the public. It is still inhabited by members of the

royal family.

Leaving Tetouan, we

drove through more mountains and lush valleys, finally arriving at the

Mediterranean Sea for a late lunch and a walk on the beach.

Leaving Tetouan, we

drove through more mountains and lush valleys, finally arriving at the

Mediterranean Sea for a late lunch and a walk on the beach.

TANGIER, once an international city that drew adventurers, artists and writers, has a special character that sets it apart from other Moroccan cities. It is a port city, dominated by its medina, and the main link between Africa and Europe. Its history has included Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Arabs, Berbers, Portuguese, Spanish and English, and 30 years under international administration before the city was returned to Morocco in 2014.

The twisting, turning lanes of Tangier’s medina beg for a GPS – good thing we had a local guide to get us in and out. The narrow streets are filled with interesting people as well as stalls and stores selling artisanal goods – traditional items as well as Moorish-modern designs.

The twisting, turning lanes of Tangier’s medina beg for a GPS – good thing we had a local guide to get us in and out. The narrow streets are filled with interesting people as well as stalls and stores selling artisanal goods – traditional items as well as Moorish-modern designs.

The medina wraps

around the Kasbah, which overlooks

the harbor and the Strait of Gibraltar. Every Moroccan town has a kasbah where either the ruling sheik or king once lived, providing

a high vantage point to watch for approaching and unwanted guests. Kasbahs

have long fulfilled the role of fortified castles, places of refuge from attack

for people and animals, and protection from the cold and other threats to

safety.

The road from Tangier to Rabat hugs the coastline and much of the land is agricultural. The most striking man-made structures were greenhouses, growing everything from avocados to bananas to tomatoes to zucchini. This requires less water than open fields and provides a year-round source of important foods.

RABAT is a city of domes and minarets,

sweeping terraces, wide avenues and green spaces. It is the political, financial, and administrative capital of Morocco; pictured here is the Parliament building. Rabat is home to the country’s largest university and is its second

largest city. Archaeologists have shown that this area was once occupied by the Romans. Large numbers of Moors

came from Andalusia in 1610 when Philip III regained the throne of Spain. Rabat has been recognized as a World Heritage Site, a visible symbol of a heritage shared by

several major cultures – Roman, Islamic and European.

Rabat's kasbah

and medina form a compact cornerstone

of the city, which is bounded by the sea and river on two sides and by high

walls on the others. Within these boundaries, narrow streets lead through the souks

(markets), to the storybook kasbah

and the quiet walks of the Andalusian Garden.

The Oudayas Kasbah is a small, beautiful old kasbah with blue-painted walls and tiny shops; it takes its name from an Arab tribe that once lived here. Part of the city walls that surround this one-time fortress, as well as the gate that pierces it, date from 11th-12th century. Beyond the gate, there are beautifully carved and decorated doorways. The El-Atika Mosque, on the main thoroughfare, was built in the 12th century and is the oldest mosque in Rabat.

Tucked inside the old palace grounds are the Andalusian Gardens, a quiet, secluded place

designed by a French landscape architect in the twentieth century. The gardens give the

impression of being abandoned, with its structures in need of restoration,

but it still has a certain charm. Not far from the gardens is a large cemetery, said to be the final resting place of many famous Moroccans. We couldn’t read a single name (written in Arabic), but we did admire the beautiful tilework.

The medina is the maze-like old city wrapped

around the base of the kasbah. The Andalusian

Wall is a portion of the medina

wall built in the 17th century, when Muslim refugees fled southern Spain for

North Africa. The refugees included talented artisans as well as the nucleus of

a pirate empire bent on revenge against Spain.

They built a settlement reminiscent of their homeland at the base of the

kasbah. The Andalusian wall stands about 20 feet high

and is punctuated by five major gates with high arches.

The medina itself is teeming with

activity. Some of the streets were quite

crowded; all were quite colorful and people were generally friendly and

welcoming. Too bad they don’t speak

English – we could have used some help getting out of there …

The Royal Palace is an extensive complex

enclosed within its own walls and mostly closed to the general public. The exterior is quite impressive, particularly

the Gate of the Winds. The palace was built on the site of an 18th century royal residence; today it houses the offices of the Moroccan government, the

Supreme Court, the prime minister’s office, the ministry of religious

organizations, and the El-Fas Mosque. This

is the main palace and is one of many palaces throughout the country. Traditionally, the king resided here in the harem

with his wives, but the current monarch (Mohammed VI) stays in one of his own

private residences.

Chellah is an ancient site originally settled by Phoenicians and

rebuilt by Muslims in the 13th century. It was initially a fortress before it was

chosen in 1284 by Abou Yacoub Youssef (an early Muslim ruler) as the site for a

mosque and the burial place of his wife.

He also was buried here, as were several of his successors who

embellished the burial complex and built walls around it.

Within the walls are

the ruins of Carthaginian and Roman buildings, as well as the mosque, a monastery,

and a pool of eels. After the necropolis

was abandoned, it was ransacked several times and largely destroyed by

earthquake in 1755.

Chellah's gardens have run wild and colonies of

storks have taken over the trees and the minaret. One of

the niftiest places we visited - it has it all - Roman and Muslim ruins, storks and eels!

The opulent Mausoleum of King Mohammed V, who died

in 1961, was built beside this centuries-old landmark. it is the final resting place of three

members of the royal family and is both a tomb and a mosque. The Mohamed V Mausoleum is one of the few

holy places in Morocco that are open to the public. King Hassan II commissioned the construction

of the mausoleum for his late father in 1962; construction was completed

in 1971. Both of King Mohammed’s sons

(King Hassan II and Prince Abdallah) are buried alongside him.

The building features white walls and green-tiled roof. The interior is finished in white marble and granite floors and walls and a beautiful granite block with a headstone indicates the final resting place of the great king. The doors and ceiling are carved in beautiful motifs and designs. Traditional artistic techniques combine with a touch of modern design to create a wonderful display of tilework and stucco sculpture.

The building features white walls and green-tiled roof. The interior is finished in white marble and granite floors and walls and a beautiful granite block with a headstone indicates the final resting place of the great king. The doors and ceiling are carved in beautiful motifs and designs. Traditional artistic techniques combine with a touch of modern design to create a wonderful display of tilework and stucco sculpture.

Not far from Rabat, we stopped a while in the town of Khemisset for an educational visit to the local fruit and vegetable market. The market was “housed” in a makeshift array of stalls, poles and sheets of plastic, and it was chock full of fresh, luscious items to make us all hungry.

Around the edge of

the market, there were groups of women selling fresh milk. Note bottles of every size and shape.

Inside the market folks were selling every imaginable type of fruit and/or vegetable. Hard to decide which was more interesting, the food or the people themselves. They were most welcoming, though not everyone was up for having a photo taken.

Inside the market folks were selling every imaginable type of fruit and/or vegetable. Hard to decide which was more interesting, the food or the people themselves. They were most welcoming, though not everyone was up for having a photo taken.

FEZ is the oldest of Morocco’s imperial cities, its second largest city and

its cultural and spiritual capital. Founded

in the 9th century, Fez reached its height in the 13th–14th

centuries, when it replaced Marrakesh as the capital of the kingdom of Morocco.

Its medina has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Our lodging was the Riad Dar Dmana, located in the heart of

the medina of Fez. This jewel of

Hispano-Moorish architecture is over 400 years old and has been completely restored while maintaining the

architecture and traditional building materials. The feeling here is not so much a hotel as a

refined, elegant house where the owner, his family members and staff, welcomed

us in a family atmosphere. The stained-glass windows in our room, the

tile-work and chiseled plasters all were enchanting, a trip back in time to another

world.

On a hill overlooking Fez, there is an old fortress and tower offering a panoramic view over the Old Medina and its environs. We had heard that the Fez medina was quite large, but its expanse is hard to take in – the medina itself is sprawled all over the countryside. It's easy to get lost in there.

On a hill overlooking Fez, there is an old fortress and tower offering a panoramic view over the Old Medina and its environs. We had heard that the Fez medina was quite large, but its expanse is hard to take in – the medina itself is sprawled all over the countryside. It's easy to get lost in there.

The city walls seem to go on forever, with

all manner of gates for entrance and exit.

The holes in the walls are to hold scaffolding for maintenance

and repair; most of the time they are occupied by pigeons.

The medina is a walled-in, wall-to-wall urban beehive, a city within the city, where half a million people live and work. Fez was founded between 789 and 808 AD by Idriss I, the grandson of the prophet Mohammed, This intricate maze of streets lined with open markets, shops, schools, fondouks (hostels or rest stops for travelers), palaces, residences, riads, mosques and fountains. Its narrow streets, 13th-century buildings and busy markets are hidden by the massive walls that were built to defend against attacks.

Today no motorized traffic is allowed in the old city; the medina ranks as the largest car-free plaza in the world. Donkeys and mules are commonly used for transportation in the old city's maze of narrow streets, which lead to bustling markets and souks.

Founded in the 9th

century, the Fez medina is home to the University of Karueein, the oldest existing

and continually operating educational institution in the world. Here students have studied theology,

jurisprudence, philosophy, mathematics, astrology, astronomy and languages.

Since the middle ages, the university’s students have included famous people

from all around the Mediterranean Sea.

Founded in the 9th

century, the Fez medina is home to the University of Karueein, the oldest existing

and continually operating educational institution in the world. Here students have studied theology,

jurisprudence, philosophy, mathematics, astrology, astronomy and languages.

Since the middle ages, the university’s students have included famous people

from all around the Mediterranean Sea. Also within the medina is the Medersa el-Attarine, a former Islamic school. Like all religious buildings in Morocco, it features five elements of design: marble, carved cedar, chiseled plaster, calligraphic inscriptions, and zellige tilework. None of this ornamentation depicts animals or humans as Islamic law forbids it. No icons or idols are allowed to stand between man and Allah.

The medersa was established in

1325, and students would come here to study with the goal of memorizing the Qur’an.

This could take years, as this religious text contains more than 6000

verses spanning 114 chapters. Some

students would move on to become imams,

or Islamic scholars and leaders of worship.

The medersa was established in

1325, and students would come here to study with the goal of memorizing the Qur’an.

This could take years, as this religious text contains more than 6000

verses spanning 114 chapters. Some

students would move on to become imams,

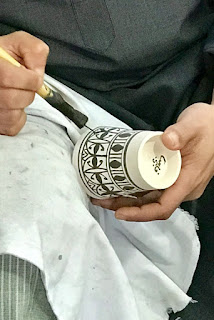

or Islamic scholars and leaders of worship.  In the Potters’ Quarter, we visited a pottery

co-operative, which highlighted the art of Moroccan pottery as well as the

process of zellige, or Moroccan tilework.

In the Potters’ Quarter, we visited a pottery

co-operative, which highlighted the art of Moroccan pottery as well as the

process of zellige, or Moroccan tilework. Pottery-making starts with soaking the clay in water for a week, then kneading it first by foot (think “stomping grapes”), then by hand in order to release air bubbles and create a soft, pliable material. Fez pottery is shaped by hand, the pottery wheel is turned by foot for complete control, and a fine thread or piece of wire is used to cut the shape from the wheel. Once the desired shape has been formed, it is set out in the sun to dry. Pieces are painted by talented artists before firing in kilns fueled by crushed olive pits.

The final products

are beautiful and all seem to be in search of a forever-home. Quite a few people came away with big

bundles…

Traditional Moroccan tilework (zellige), was equally fascinating; full of beautiful geometric patterns, elaborate mosaics are a distinct feature of Moorish or Moroccan architecture. Historically, colorful tile has been used to decorate homes as a statement of luxury and the sophistication of the inhabitants. It is typically a series of patterns utilizing colorful geometric shapes. This framework of expression arose from the need of Islamic artists to create spatial decorations that avoided depictions of living things, consistent with the teachings of Islamic law. The process is tedious and requires painstaking attention to detail, but the products of these artisans are wonderful.

Note that the work is done with the color side down - it is truly amazing that these guys turn out perfect pieces when they can't see the final product until it is turned over. Amazing

Leather tanning is a craft with traditions that go back

thousands of years, and the tanneries of Fez are well-known for turning animal

hides into soft, rot-proof leather. The

hides of sheep, goats, cows and camels undergo several processes including the

removal of hair and flesh. This is

followed by soaking in vats, then by drying and rinsing, before they are ready

to be dyed and handed over to leather-workers.

The process is fascinating to watch, but the smell is almost unbearable

– our guide gave us sprigs of mint to hold under our noses.

Vats, some of which

have been in use for centuries, are used for soaking the skins after the flesh

and hair have been removed. The tanning solution that turns them into leather

is made from the bark of mimosa or pomegranate.

The tanned hides are

hung out to dry on the terraces of the medina.

Roofs of houses, hillsides, even cemeteries, may be used in the drying

process.

The dried hides are

rinsed in generous quantities of water.

They are then softened by being steeped in baths of fatty solutions. Natural pigments,

obtained from plants and minerals, are still used by Moroccan craftsmen to

color the hides.

Dyed leather is used

to make many useful and decorative objects such as bags and clothing. These goods are offered for sale in the

numerous souks in the medina of Fez.

Textiles are one of the most respected Moroccan art forms,

especially rugs and fabrics that are ornately decorated and superbly designed. Morocco's textile heritage dates back hundreds

of years. Traditionally, textiles have been an art reserved for women,

especially those of wealthy families. Young women would be taught this art form

very early in life and would continually practice. Across history, control over

this important industry actually gave women a degree of economic and social power, something they were often otherwise denied. Young women were expected to produce several pieces for special occasions as a way to demonstrate their education and maturity. Once married, these women would produce textiles for their home and engage with other women to share techniques, styles, and ideas.

Moroccan weaving tends

to favor geometric and abstract patterns. These patterns are chosen for their

aesthetic values of symmetry and harmony rather than direct representation of

earthly objects and ideas. Still, there is a deep meaning within these

patterns. Embroidered textiles are found across all aspects of Moroccan life,

from walls to floors to bags to clothes. Babies are swaddled in embroidered cloths,

families are clothed in embroidered fabrics, and the dead are covered in

embroidered shrouds.

Weaving shops are

often family owned, with a master weaver supervising other weavers. Men mostly work at these large horizontal looms. They generate an

amazing array of fabrics, scarves, sashes, belts – and try hard to convince us that

we cannot get along with without some of each.

Pottery, textiles and

leather are just three of the traditional

markets, or souks, found in the medina.

In fact, the medina is full of souks

that specialize in various types of goods.

In theory, each specialty is housed in individual sections, each one leading

to the next. Craftsmen and sellers are

grouped together by the products they offer, and each type of craft has its own

street, usually surrounding the main mosque or kasbah. It sounds logical,

but the result is hopelessly complex to the uninitiated – we settled for

wandering around trying not to get lost.

The souks in Fez are said to be the largest and most confusing souks in

all Morocco. We believe it.

The Jewish Quarter of Fez, known as the mellah, is thought to be the first

Jewish enclave to be established in Morocco.

The rulers of Fez promised to protect the Jewish community in return for

an annual levy collected by the state treasury.

The quarter was located near the palace for greater security. With its souks,

workshops, schools, synagogues and a cemetery, the Jewish Quarter

flourished. Walking the narrow streets,

this area looks like anywhere else in the medina – the defining difference here

is the presence of balconies (Muslim homes did not have balconies – another way

to keep women from being seen by others).

The Danan Synagogue is among the oldest in

North Africa. Today, only a few dozen Jewish families remain; the Jews of Fez

mostly migrated to Casablanca or Israel.

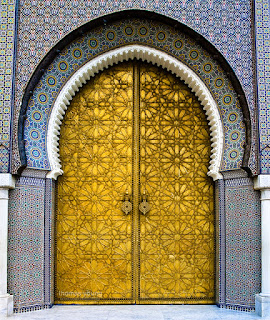

The Royal Palace is a complex surrounded by

high walls and covering nearly 200 acres.

It was the main residence of the sultan, his guard and his retinue of

servants. It was also where the dignitaries

of the central government came to carry out their duties. Part of the palace is still used by the king

when he stays in Fez.

There are seven magnificent doors – one for each day of the week. They are made of cedar and covered with bronze; the closed doors create a commanding row of golden shields. Its knockers are decorated with symmetrical 8-pointed stars, which symbolize harmony and paradise in Islam.

We resisted the urge to knock – the doors are permanently closed. It’s enough to admire the artistry of the doors and exterior walls. But it does make one wonder what’s inside …

Our home-hosted dinner in Fez was unlike

any other – it was a girls’ night out.

Five women from our group went for dinner with four women of Fez – a

mother, two daughters, and one granddaughter.

They lived in a traditional Moroccan home – a two-floor U-shaped

building with a lovely courtyard, beautiful tilework, carved ceilings, and

elegant rooms.

Mom was a superb cook (dinner was excellent) and the grandkid was a born entertainer. They told us about their lives, their jobs, their family. One of the daughters was recently engaged to be married, and we learned that Moroccan tradition is to throw a big engagement party – the wedding is just a simple civil ceremony. They played a video-recording of the engagement parting and dragged us into the middle of the room to learn how to dance. The mom put us all to shame, but it was good fun and lots of exercise.

Mom was a superb cook (dinner was excellent) and the grandkid was a born entertainer. They told us about their lives, their jobs, their family. One of the daughters was recently engaged to be married, and we learned that Moroccan tradition is to throw a big engagement party – the wedding is just a simple civil ceremony. They played a video-recording of the engagement parting and dragged us into the middle of the room to learn how to dance. The mom put us all to shame, but it was good fun and lots of exercise.

VOLUBILIS AND MEKNES are two cities located near the foot of the Atlas Mountains, at the heart of the agricultural area that has been Morocco’s grain store since ancient times. The historical importance of the two cities can be seen in the ruins of Volubilis, the most important archaeological site in Morocco, and in the grandeur of the Moorish buildings in Meknes. The drive from Fez to Volubilis took us through rolling hills, farms and orchards.

VOLUBILIS, an ancient town at the foot of the mountains in a

sweeping valley filled with olive and almond trees, is the crown jewel of

Morocco’s Roman ruins and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This

former city of 20,000 was settled in about the 3rd century BC and

prospered until the year 40 AD. The

sprawling floor plans and brilliant mosaics of its buildings suggest this was a

city of great wealth. Temples and other

structures from the Roman era have been uncovered, and there is plenty more

here for archaeologists to explore.

The site is dominated

by the remains of the grand public buildings around the forum, with the

impressive arches of the basilica

(courthouse) arranged in front of pillars of Jupiter’s temple – now topped with stork nests. Every old ruin in Morocco seems to host its

own population of these large black-and-white birds, which soar overhead or

preen in their nests.

A triumphal arch, commemorating Emperor

Caracalla, marks the beginning of the city’s main street. Lined with shops, the Decumanus Maximus was the most desirable address in town.

Expansive villas boast the colorful floor mosaics that have made the ruin famous: House of Orpheus, House of the Athlete, House of the Dog, and House of the Ephebe.

Expansive villas boast the colorful floor mosaics that have made the ruin famous: House of Orpheus, House of the Athlete, House of the Dog, and House of the Ephebe.

Much of the town’s

wealth came from olive orchards and wheat fields, but the other main export was

wild animals, including lions, jaguars and bears that went to fight and die in

Rome’s Colosseum. Within just 200 years,

the beastly population of the area was devastated, and indigenous species like

the Barbary lion and Atlas bear had all but ceased to exist.

After Rome withdrew from Volubilis, the city declined. When the Arabs arrived in the 8th century, Christian inhabitants of Volubilis were still speaking Latin. The city was soon Islamized, although its

structures remained in good shape until the 18th century when Sultan

Moulay pulled them down to use for his palace in nearby Meknes.

From the time it was

founded in the 10th century until the 17th century, MEKNES was overshadowed by

Fez, its neighbor and rival. This changed

in 1672, when Moulay Ismail made Meknes became an imperial city. The sultan tirelessly built gates, ramparts,

mosques and palaces. His building plan

involved robbing the ruins of Volubilis and the Badi Palace in Marrakesh. Today Meknes is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The medina is

encircled by a wall 25 miles long, giving it the appearance of a sturdy

fortress set with elegant gates. Bab Mansour is the most spectacular

entrance to Moulay Ismail's new city. It is considered one of his greatest

works and is the largest gate in North Africa. It is ranked among the four most

beautiful doors in the world. Note the

columns that were brought from Volubilis.

Another impressive memorial to Moulay Ismail is the Royal Stables. This massive stable yard was constructed to house twelve thousand horses. The sultan’s horses were waited on hand and foot, with a groom and a slave for each horse, to ensure that all their needs were met and stables kept in immaculate condition. Today, most of the stables are in ruin and due to an earthquake during the eighteenth century, the roof of the stables no longer provides protection. Even so, its sheer size is amazing, not to mention the effort that was put into the construction.

The sultan constructed granaries to store horse feed; they held enough grain to feed the horses for twenty years! To store such large amounts of grain, the granaries needed to be kept cold, and for this, the granaries were constructed with thick walls and a suspended forest was grown on the roof. Water from the reservoir below, was forced through ducts in the floor, to maintain a low temperature and keep the grain from rotting.

The MIDDLE ATLAS MOUNTAIN RANGE covers a vast area, lying just south of Fez

and Meknes and running towards Marrakech. It is a wild region of great

beauty: often covered in thick forest,

with oak and cedar prevalent in the north, it is home to lakes, the Barbary

“ape” (really a macaque) and numerous Berber towns, many of which are rarely

visited by tourists. It is the most fertile of the Atlas ranges and runs

for around 220 miles south of Fez and Meknes. Although lower and

generally less craggy than the High Atlas range, it has several peaks near

10,000 feet.

The MIDDLE ATLAS MOUNTAIN RANGE covers a vast area, lying just south of Fez

and Meknes and running towards Marrakech. It is a wild region of great

beauty: often covered in thick forest,

with oak and cedar prevalent in the north, it is home to lakes, the Barbary

“ape” (really a macaque) and numerous Berber towns, many of which are rarely

visited by tourists. It is the most fertile of the Atlas ranges and runs

for around 220 miles south of Fez and Meknes. Although lower and

generally less craggy than the High Atlas range, it has several peaks near

10,000 feet.

IFRANE is a squeaky-clean pseudo-Swiss town, with its

slanted, russet-tiled roofs hidden amidst a cedar forest which covers the

hills above 5200 feet. The town was

established during the French protectorate and has a distinctly European

character. It is mainly a winter ski resort and a summer hideaway for rich

Moroccans wishing to escape the hustle and heat of the large cities. The king has a summer residence here. We stopped here for a coffee break and were

lucky to spot Barbary macaque sunning in the park.

Somewhere between

Ifrane and Midelt, we stopped to visit a

semi-nomad family. They are

considered semi-nomads because they only move a couple of times a year, between

a warmer-weather dwelling in the mountains and a milder location in the valley

for wintertime. The family included

husband and wife, their grown son, two divorced daughters and several

grandchildren.

They live in a makeshift sort of shelter – part tent, part lean-to. Most of the buildings and enclosures are for their sheep. Their Moroccan sheep dog keeps a close watch on everyone. It’s a hard life – impossible to imagine what it’s like living in such a harsh environment with such flimsy shelter and so few resources.

They live in a makeshift sort of shelter – part tent, part lean-to. Most of the buildings and enclosures are for their sheep. Their Moroccan sheep dog keeps a close watch on everyone. It’s a hard life – impossible to imagine what it’s like living in such a harsh environment with such flimsy shelter and so few resources.

MIDELT is a market town in the Middle Atlas Mountains; it became a French

garrison town during the Protectorate. Villages

near the town have buildings typical of Southern Morocco.

The main commercial activity in the area is farming. There are lots of sheep, and we enjoyed a chat with a shepherd who was thrilled that these crazy Americans were taking pictures of his sheep.

ZIZ GORGE was created by the Wadi Ziz, which springs in the heart

of the High Atlas, carves through the mountains, irrigates fertile farmland,

and then disappears in to Saharan sands.

Lots of dates grown here.

ERFOUD is a peaceful village, an oasis town in eastern Morocco, known as the Gate of the Sahara Desert. Many fortified villages have existed in this area for centuries, but Erfoud was built by the French in the 1920s. Berber tribes in the area put up a long, drawn-out resistance to French rule, and this valley was one of the last regions of southern Morocco to surrender. Erfoud’s main sources of income are dates and fossils.

There are many oases in southern and eastern

Morocco. Their existence depends on

water, which is either supplied by rivers flowing down from the mountains or by

an underground water table. Underground

water rises naturally at the foot of dunes or is pumped by artesian wells or

along underground channels. These

channels are used for irrigation, leading to a chain of oases along river

valleys in the desert. The oasis was

once a welcome stopping place for caravans, but today the inhabitants rely on

it for their livelihood. The 800,000

date palms that grow here are renowned for their fruit. Dates are considered symbols of happiness and

prosperity, and they figure in many rituals, including birth, wedding and

burial ceremonies.

RISSANI is a small town on the edge of the Sahara. The Rissani souk is one of the most famous markets in the area – donkeys,

mules, sheep, goats, dates, vegetables, spices, jewelry, daggers, carpets

baskets, pottery, leather, you name it.

This was once a thriving city of 100,000 inhabitants; it is now only

about one-third of that. Lack of water

led to mass exodus and hard times, but the locals were happy that we stopped to

wander around, check out the souk, and do a little people-watching.

One of the most entertaining stops was a place that sold jellabas and caftans and other traditional clothing. Several in our group came away with fine new outfits; others settled for a photo-memory.

We also grabbed

photos of some interesting road signs

…

One of the most entertaining stops was a place that sold jellabas and caftans and other traditional clothing. Several in our group came away with fine new outfits; others settled for a photo-memory.

The SAHARA DESERT is the world’s largest hot desert and the third largest desert overall (after Antarctica and the Arctic). Its area of 3,600,000 square miles, covers much of North Africa, and is comparable to the area of China or the USA. The vast majority of the Sahara is made up of large expanses of sand, but there are some (few) mountains and grasslands. We headed for the Erg Chebbi Dunes, which rise up out of the stony, sandy desert, extend for some 20 miles, and reach a maximum height of 820 feet. They are the most accessible large dunes in the country – somewhere out there is our camp home for the next few days.

Our main desert

transportation was in four-wheel drive SUV’s.

Our driver was named Mohammed; he spoke Arabic, French and a little

English. He gave us a heck of a ride

…

The OAT DESERT CAMP is located near one side of the Erg Chebbi Dunes. It consists of 12 canvas tents with camp beds and chairs and come equipped with semi-attached bathroom facilities. There is a separate dining tent and a central gazebo for shade.

The staff had laid

rugs between all the tents, to minimize tracking of sand into our luxurious

living quarters. Unfortunately, they

didn’t stay put for long – our first desert experience was a sandstorm! Exciting for a while, but not good for humans

or cameras. Thankfully, it didn’t last

too long and no real damage.

Nory took

us to visit another semi-nomad family. He has taken a special interest in this

family because the husband (head of the family) had died a few months

before. His wife, two daughters and

several grandchildren were struggling to stay alive in their home – a couple of

adobe buildings, a tent and some sad-looking livestock. In Muslim tradition, a widow can’t be seen by

other than family for an extended period of time, so she was secluded in one of

the back rooms. The daughters offered us

tea, but we didn’t stay long – just visited outside, gave the little girl a bag

of chocolate, and Nory gave them some cash. One can only wonder what will

become of these folks …

From the nomad family

to the fossil beds! The Sahara Desert was once at the bottom of

an ancient ocean. Today, it seems to be

miles of sand, but there are also lots of rocks, some volcanic and some sedimentary. In the sedimentary rock, it’s not too hard to

find fossils – squid, ammonites (like snails), and trilobites (extinct marine

arthropods, like lobsters without the big claws). They are between 300 and 500 million years old! The trick is to find a fossil in a rock that

isn’t as big as a house and buried in tons of sand – we saw many fossils, but

not much small enough for souvenirs.

Fortunately, fossil shops also are easy to find. We stopped at one that provided an interesting and educational tour – before dropping us off in the showroom. The folks haul in giant pieces of fossil-filled rock, slice them into manageable pieces, and painstakingly polish or carve out the fossils.

Fortunately, fossil shops also are easy to find. We stopped at one that provided an interesting and educational tour – before dropping us off in the showroom. The folks haul in giant pieces of fossil-filled rock, slice them into manageable pieces, and painstakingly polish or carve out the fossils.

The products of this work are incredible: tables, sinks, bowls, and beautiful stand-alone, very old fossils. Thankfully, some of these were small enough to fit into our already-bulging luggage – a wonderful souvenir of our first day in the Sahara.

After dinner, most folks headed to bed – it had been a couple of long days and we wanted a good rest before setting out to further explore the Sahara. Plus, we also wanted to get up in time to see the sunrise. Sky was a bit cloudy but still worth the effort to get out of bed early. Sunrise also provided a chance to see the tracks of friendly natives who had been wandering around the camp while we slept.

A full day to spend in the Sahara! First stop was at a farm. We were unaware than anyone might attempt farming in the Sahara Desert – wrong. The government makes the land free (or almost free), farmers pay no taxes, and it turns out that there is water underground here.

Nory’s farmer friend (Mohammed) and his grandkids showed us around. They grow a little bit of everything, from olives to dates to grain for livestock to vegetables for the humans.

Dates are the money crop. Mohammed showed up how he pollinates the date flowers for the best fruit – and then he proceeded to hop up the nearest tree to show us how to reach the flowers and later the fruit. No ladders needed here!

This is all made

possible by a well and an elaborate irrigation system – all sorts of channels

and diversions to carry water to different parts of the farm. This water is a bit salty, so the family gets

its drinking water from another well some miles away – his daughter uses their

donkey to fetch water every day.

This is all made

possible by a well and an elaborate irrigation system – all sorts of channels

and diversions to carry water to different parts of the farm. This water is a bit salty, so the family gets

its drinking water from another well some miles away – his daughter uses their

donkey to fetch water every day. After the farm visit, we were ready to see the desert up close and personal. Time for a camel ride. The beasts were ready and waiting for us, but first our driver had to be sure our head scarves were just right – in case of another sand storm.

The nicest part of the camel ride was the end - it was pure relief to get off that dromedary. That said, it was a wonderful experience - pure Sahara!

After the camel ride,

we visited a Muslim cemetery near

a deserted town on the Algerian border.

We had seen several cemeteries, but none quite as stark

as this lonesome spot in the desert.

Graves are not marked with names, but the orientation of the stones

tells whether the deceased was male or female.

Khamlia is a small desert village inhabited by Gnaoua Berbers who

have been living there for generations.

Somehow, they have eked out an existence from the scorched land where

temperature can reach up to 127°F in the height of summer. A new paved road into the village has

provided the opportunity for these folks to showcase some of their traditional

songs, dances and costumes. Check out the short video below.

Khamlia is a small desert village inhabited by Gnaoua Berbers who

have been living there for generations.

Somehow, they have eked out an existence from the scorched land where

temperature can reach up to 127°F in the height of summer. A new paved road into the village has

provided the opportunity for these folks to showcase some of their traditional

songs, dances and costumes. Check out the short video below.Back in camp for a late lunch and some free time and then a cooking lesson from the camp chef who showed us how to make chicken tagine. This traditional dish has many ingredients and is cooked in a special earthenware pot (also named tagine). We took careful notes – we have tried to make it at home, but just doesn’t taste the same.

Before dinner, we

headed out into the dunes again (this time by motor vehicles) to find the

perfect spot to watch the sunset. Nory

knew just where to take us. We pitched

our shoes and climbed to the top of the nearest dune.

Perfect spot for a group picture - taken by our guide, Nory.

We weren’t alone for

long. Within minutes, four young women

from a nearby nomad camp showed up and spread their wares; they never said a

word, but several folks bought bracelets they’ll never wear. Hard not to help these folks any way you can.

Perfect spot for a group picture - taken by our guide, Nory.

Sunset was quite nice – the sand takes on yellow, orange and red colors, as do the people. It’s a magical/mystical experience just to be standing in the middle of the Sahara Desert, watching the sun set. Who would have thought we'd be there?

Just as the sun was

gone from view, we were passed by a woman who had been out all day searching for

places to let her goats graze and trying to gather firewood. She had a lot more goats than firewood. Once again, we are struck by the hardship of

living in this place.

For our last evening

in the desert, the camp staff and Nory, serenaded us with traditional music –

and a little dancing as well. Lots of

drums, lots of noise – good thing we’re in the middle of nowhere.

Leaving the desert,

we soon entered the High Atlas Mountains, the largest and most dramatic range

in Morocco, with several peaks over 10,000 feet and some over 13,000 feet. The range has North Africa’s highest peak,

Jebel Toubkal (13,671 feet), which lies within the Toubkal National Park. The High Atlas range runs for over 400 miles

from the Atlantic coast eastward, to Marrakech and beyond. Its sharp peaks,

deep valleys, and high plateaus create a dramatic landscape. There are many remote Berber villages and farms against the mountain backdrop.

TINEJDAD, at the Ferkla

Oasis, is home to the Ksar El Khorbat Oujdid, which was built around 1860. A ksar

is a fortified village, developed originally as a communal stronghold to protect against raids by bandits and nomadic

tribes that came after harvests had been gathered. Over time, it expanded to become a village,

with houses, a mosque, granaries, and sometimes an

inn.

Built of piseʹ (compressed clay), this ksar is still inhabited and has kept its architecture and atmosphere of yesteryear. There is no concrete or brick construction; the traditional and original materials have been scrupulously preserved.

The complex has one

main alley and a number of side alleys. The houses were built over the alleys

so the alleys are cool. This ksar has a special artistic value

because of the structure of its covered streets, absolutely rectangular, with

shafts of light at intersections. The main and the side

streets are mostly shaded by the first floors of the houses. Only the crossings

are not; so they appear like fountains of light and give the whole ksar a mysterious look.

This ksar now is being restored by a local

association with the help from international groups and private investors. The association has offices inside the Ksar

and conducts various activities that to boost economic and cultural life of its

inhabitants: crafts, preschool courses, literacy courses for women, and art

exhibitions. We stopped by the nursery

school and the bakery before heading to the museum.

The Oasis

Museum occupies three

restored houses inside the Ksar El Khorbat Oujdid. Its exhibits present the traditional

life of the region and its evolution over the centuries. It includes 22 rooms, each dedicated to a

specific topic of traditional life in an oasis in the southern part of the High

Atlas. Nory says it is the best museum

in Morocco; we don’t have much to compare, but it was a very interesting visit.

The El Khorbat Restaurant is located inside

the palm grove at the bottom of the Ksar

El Khorbat. It is located on a wide terrace between palm trees and is

protected from the sun by roofs of logs and clay. The dishes are prepared by the women of the ksar, following traditional recipes of

the region and maintaining the flavor of former times. The specialty of the

house is the tagine with dromedary

meat and dates, but we settled for something a bit tamer … maybe chicken.

OUARZAZATE is a former garrison town of the French Foreign Legion; it was founded in 1928 as a strategic base from which to pacify the south. Today it is a peaceful provincial town with wide streets, lots of hotels, and municipal gardens. It is home to Ait Benhaddou, a ksar standing on the bank of the river Wadi Mellah and backed up to a pinkish sandstone hill. This picturesque village was built near water and arable land, fortified and in a place safe from foreign attack. Since it was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site, some of its buildings have been partly restored.

Today, the remaining

residents live across the river, where they plow the land, work the fields, and offer tours to visitors. They work hard, farming without machinery,

using old traditional methods.

One man is an artist, painting local scenes with a magic paint that deeps in color when heated over a gas burner. Several members of our group took one of these home with them.

One man is an artist, painting local scenes with a magic paint that deeps in color when heated over a gas burner. Several members of our group took one of these home with them.

Here, too, is the Imik Smik Women’s Association for Rural

Development, established in 2012 to

teach girls and women how to sew, read, cook, and to develop healthcare and

further education that otherwise would not be available. Sponsored by Grand

Circle Foundation, the Women’s Association generates funding by selling bread,

pastry, and couscous to local guesthouses in the village.

A couple of the women provided information about the group’s history

and current efforts. At this time, in addition to selling food, they have

started a kindergarten for members' children.

The group has about 20 members from the village population of 150

families. They are working hard to

change their lives and those of the young women in their community, for the

better.

We also “helped” make cookies and couscous before enjoying a home-hosted meal of (you guessed it) – Chicken Tagine.

After lunch, we learned a bit about henna, a dye which has been used since antiquity to dye skin,

hair and fingernails, as well as fabrics including silk, wool and leather. Henna parties usually take place within the

week before a special occasion, such as a wedding or baby showers. We had a pretend wedding, and most of the

women in our group came away with a lovely, but temporary, tattoo.

MARRAKESH, the Red Pearl, was founded by the tribe of Muslim

Berbers known as Almoravids – warrior monks from the Sahara. They carved out an empire that stretched from

Algiers to Spain, with Marrakesh as its capital. Today it is Morocco’s fourth largest city, known

for its rich history, its fabulous palaces, its dusty pink walls, and its

luxuriant palm grove.

The Riad Nesma was our hotel, located in the medina of Marrakesh, only a short distance from the main market square. It also was some distance from the road where the bus stopped - no cars (or buses) allowed in the medina. Our guide arranged for special transport for our luggage.

The Riad Nesma was our hotel, located in the medina of Marrakesh, only a short distance from the main market square. It also was some distance from the road where the bus stopped - no cars (or buses) allowed in the medina. Our guide arranged for special transport for our luggage.

The riad is built in traditional Moroccan style around a central courtyard - open to the sky. It seemed that we had been invited into the home of a Moroccan noble family in the 17th century – ornately painted ceilings, arched doorways hung with white curtains, tiled floors, and intricate ironwork covering the interior windows overlooking the beautiful patio.

Each of the guest rooms is individually designed and decorated. Our room was charming and included views of the inside of the building and of the street in the medina outside - quite a contrast.

The Medina of Marrakesh dates from the 11th

century. but it includes architectural and artistic masterpieces from different

periods in history. These structures are

some of the reasons that the medina has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site: 12

miles of ramparts and gates (in pinkish clay, like most of the original

structures), - the Koutoubia Mosque with its 250-foot high minaret, the Saadian

tombs, and the Djemaa El-Fna square.

The ramparts of Marrakesh completely

encircle the medina. From the time of

its foundation, Marrakesh was defended by sturdy walls set with forts. These walls are 12 miles long, up to 6 feet

thick, and up to 30 feet high. Some of the monumental gates at pierce them are

excellent examples of Moorish architecture.

The Koutoubia Mosque was built in about

1147 by Sultan Abd el-Moumen; it is one of the largest mosques in the western

Muslim world. The minaret, a masterpiece of Islamic architecture served as the

model for the Giralda in Seville, Spain, and the Hassan Tower in Rabat. The beautifully carved minaret, topped with three gold balls, towers over the square; the

interior contains a ramp used to carry building materials to the summit. The “Booksellers’ Mosque” takes its nickname

from the manuscripts souk that once took place around it.

The Saadian Tombs constitute some of the

finest examples of Islamic architecture in Morocco. The tombs date from the late 16th to the 18th centuries; their style is very decorative, somewhere

between magnificent and ostentatious.

There are two mausoleums which are set in a garden symbolizing Allah’s

paradise.

The Jemma el-Fna Square is the main market

square in the medina of Marrakesh; it

is a unique and extraordinary place that has been the symbol and nerve center

of Marrakesh for centuries. The square

is a showcase of traditional Morocco and UNESCO has declared it a World Heritage Site. A large market is held here each morning;

medicinal plants, freshly squeezed orange juice, and all kinds of

confectionery, fruits and nuts are sold.

The square is full of people coming and going, flowing just like the

“inland, tideless sea” that writer Peter Mayne described in A Year in Marrakesh. This is the same place where countless

Saharan caravans arrived - bearing spices, salt, gold, and slaves.

After sunset, it is a gigantic, multifaceted open-air show. The square fills with musicians, dancers, storytellers, showmen, tooth pullers, fortune tellers, and snake charmers. As darkness falls, the air fills with smoke from grilling meat and the aroma of spices. Food stalls appear everywhere, selling snails in boiling water, sausages, kabobs, goat heads, and couscous.

After sunset, it is a gigantic, multifaceted open-air show. The square fills with musicians, dancers, storytellers, showmen, tooth pullers, fortune tellers, and snake charmers. As darkness falls, the air fills with smoke from grilling meat and the aroma of spices. Food stalls appear everywhere, selling snails in boiling water, sausages, kabobs, goat heads, and couscous.

Snake charmers set up camp around the square –men sitting

on carpets, surrounded by assorted snakes, including a hooded black cobra. Just lying there, less than six feet from

where we stood. We had expected all the

snakes to be contained in baskets, standing up only when they heard their

favorite melodies. And the snake charmers expect to be paid for the privilege of taking a picture, so many thanks to other travelers who shared their photos.

Magical origins aside, snake-charming is a cruel, money-making spin. When the snakes rise up to the tune of a flute, it has nothing to do with ‘being charmed’; their owners starve the creatures, feeding them only when they emerge from the basket, so that they associate the music with food. The snakes stand upright before their ‘charmer’ because they’re actually feeling threatened, and are poised to attack. Most snake charmers needn’t worry about being bitten as most of these snakes have had their fangs removed and, in some cases, their mouths sewn shut. A small gap is left for their forked tongue to flick out and to allow for small amounts of liquid to be imbibed, but the snake will only survive like this for a few weeks. Snakes have no place in ‘entertainment’. They belong nestled under a log, camouflaged in a pile of leaves or stretched out on a rock in the sun; not in a bustling marketplace, being thrust upon anyone with a camera.

Magical origins aside, snake-charming is a cruel, money-making spin. When the snakes rise up to the tune of a flute, it has nothing to do with ‘being charmed’; their owners starve the creatures, feeding them only when they emerge from the basket, so that they associate the music with food. The snakes stand upright before their ‘charmer’ because they’re actually feeling threatened, and are poised to attack. Most snake charmers needn’t worry about being bitten as most of these snakes have had their fangs removed and, in some cases, their mouths sewn shut. A small gap is left for their forked tongue to flick out and to allow for small amounts of liquid to be imbibed, but the snake will only survive like this for a few weeks. Snakes have no place in ‘entertainment’. They belong nestled under a log, camouflaged in a pile of leaves or stretched out on a rock in the sun; not in a bustling marketplace, being thrust upon anyone with a camera.

The Souks of Marrakesh are among the most

fascinating anywhere. They are laid out

in the narrow streets north and east of the main square; the historic heart of

the souks is nearest the mosque. A wide

range of goods, from fabric to jewelry and slippers, is on sale. Around this commercial hub are the crafts

traditionally associated with country people – blacksmithing, saddle-making and

basketry. Some of the best souks are:

Carpet Souk: Here one can see all sorts of carpets on display, from the more refined Arab rugs with intricate designs to the intriguing Berber carpets adorned with talismanic symbols that often tell a tribe’s story.

We also enjoyed seeing how a traditional Berber carpet is made. Berber weaving is highly dependent on women and traditionally is passed down within the home. The young apprentice is expected to learn the different looping techniques, patterns, color ranges and motifs. Colors, patterns and weaving techniques of different regions have their own distinct style and each tribe has a signature pattern.

Slipper Souk:

Perhaps the very prettiest souk in Marrakesh, here are walls of

traditional Moroccan leather slippers called babouches. There is

incredible variety, from simple and streamlined to bedazzled, embroidered and

jeweled. The bright yellow ones are meant for men, and those slippers

with a hard sole are meant to be worn outside.

Metalworking Souk: While

there are many things made of metal to buy in this souk, Moroccan lanterns take

center stage—from basic ones made from tin, to ornate beauties that take days

to make. It’s fascinating to watch the craftsman in meticulous action before

your very eyes.

Jewelry Souk: Closely related to metalworking, but also lots of individual arts and crafts sorts of jewelry. We never made to the center of the souks, where most of the gold and silver shops are located.

A symbolic hand was one of the few human-related designs that we saw anywhere in Morocco. For example, see the small charms pictured above and the beautiful hand-carved piece below. In Morocco, this is known as the Hand of Fatima, the daughter of the Prophet Mohammed; her hand is said to protect the owner from the evil eye and bring happiness to the holder. It also represents the Five Pillars of Islam: faith, prayer, pilgrimage, fasting and charity. Imagine our surprise when we spotted this card in a gift shop in Manteo, NC - who knew?

Spice Souk: The spice souk simply smells wonderful, though it’s also quite a colorful display, with spices heaped into large cones. Here you can buy a wide variety of spices at affordable prices.

We also visited a

small shop that sells all sorts of herbs and spices – those used for cooking as

well as those used for beauty and medicinal purposes.

A symbolic hand was one of the few human-related designs that we saw anywhere in Morocco. For example, see the small charms pictured above and the beautiful hand-carved piece below. In Morocco, this is known as the Hand of Fatima, the daughter of the Prophet Mohammed; her hand is said to protect the owner from the evil eye and bring happiness to the holder. It also represents the Five Pillars of Islam: faith, prayer, pilgrimage, fasting and charity. Imagine our surprise when we spotted this card in a gift shop in Manteo, NC - who knew?

Spice Souk: The spice souk simply smells wonderful, though it’s also quite a colorful display, with spices heaped into large cones. Here you can buy a wide variety of spices at affordable prices.

Woodworking Souk: Woodworkers turn out many beautiful items, mostly made from cedar wood. It was fascinating to watch young men operating homemade lathes to create handles for skewers, chess pieces, honey dippers – anything round. They used feet, hands and a length of rope to turn the piece, which was then shaped with various blades and other tools. Amazing.

Textiles Souk: There are dozens of markets and stalls selling fabrics, silks and patterns from

Morocco and around the world. You can skim through an endless selection of raw

silk, cotton, and embroidered fabrics and maybe find your exact print and color

among the hundreds of reels of cloth. In

addition to fabrics and cloths, there are ready-made outfits and a galaxy of

buttons, sequins, stones, lace and other accessories.

Leather Souk: At one

edge of the medina, the leatherworkers are busy cutting out templates for

babouches (slippers), hammering and polishing, and making up bags and satchels

from several types of animal skins. Here, too, are musical instruments and woven baskets. The tanneries, where the raw hides have been prepared

and dyed, are located elsewhere due to their unpleasant smell.

Leather Souk: At one

edge of the medina, the leatherworkers are busy cutting out templates for

babouches (slippers), hammering and polishing, and making up bags and satchels

from several types of animal skins. Here, too, are musical instruments and woven baskets. The tanneries, where the raw hides have been prepared

and dyed, are located elsewhere due to their unpleasant smell. Pottery Souk: Pottery-shopping in Marrakech is easy. Whether plain or decorated, shops here have tajine pots, vases, flowerpots, decorative objects and more stacked up outside the premises in higgledy-piggledy fashion. If you stay while, some of the stores will let you see how tile tables or ceramic lamps are made.

Food souk? The main square is the place to find lots of food stands and restaurants, but there are food shops scattered all over the place. Dried fruits were very popular (and tasty), as well as shops selling ready to eat meals in ceramic pots or tagines.

Food souk? The main square is the place to find lots of food stands and restaurants, but there are food shops scattered all over the place. Dried fruits were very popular (and tasty), as well as shops selling ready to eat meals in ceramic pots or tagines.More souks, more shops: There seems to be no end to the marketplace, and oftentimes shops pop up almost anywhere, making it hard to know which souk is where. No matter to these wanderers – the place is endlessly fascinating. There are junky souvenir shops and shops for local artists, as well as folks at work - dying yarn and painting tables. Amazing place.

Although there are more souks that you can imagine, there are many other interesting spots to explore in and around the medina. There's an old synagogue, still identifiable by the Star of David in the balcony decoration; nearby is a wall used for country votes, sorted by district of the city. There are wagons drawn by donkey and mules - the easiest way to transport goods in and out of the Medina. There is plenty to eat - even if not always identifiable. And there are quite corners to be found - residential sections or a hamman for getting a quick bath and scrub.

People-watching is another fine pastime. All sorts of folks, doing all sorts of things.

Elsewhere in Marrakech …

The Bahia Palace is a nineteenth century palace covering about 20 acres; it is

considered one of the masterpieces of Moroccan architecture, one of the major

monuments of the country’s cultural heritage.

The palace was built at the end of the 19th century under two

different sultans, father and son. The

older part contains apartments, arranged around a marble-paved courtyard. It also has an open courtyard with cypresses,

orange trees and jasmine, with two star-shaped pools. The newer part consists of luxurious

apartments looking onto courtyards planted with trees.

The best craftsmen in the kingdom were hired

to build and decorate the palace, and it is decked out with highly prized

marble, carved cedar, and handmade tiles.

The best craftsmen in the kingdom were hired

to build and decorate the palace, and it is decked out with highly prized

marble, carved cedar, and handmade tiles.

The best craftsmen in the kingdom were hired

to build and decorate the palace, and it is decked out with highly prized

marble, carved cedar, and handmade tiles.

The best craftsmen in the kingdom were hired

to build and decorate the palace, and it is decked out with highly prized

marble, carved cedar, and handmade tiles. The Jardin de Majorelle is a small, beautiful garden built by a Frenchman, Jacques Majorelle. In one corner he built a splendid Moorish villa and later added an Art Deco studio. The bright blue color throughout the garden is known as 'Majorelle Blue.'